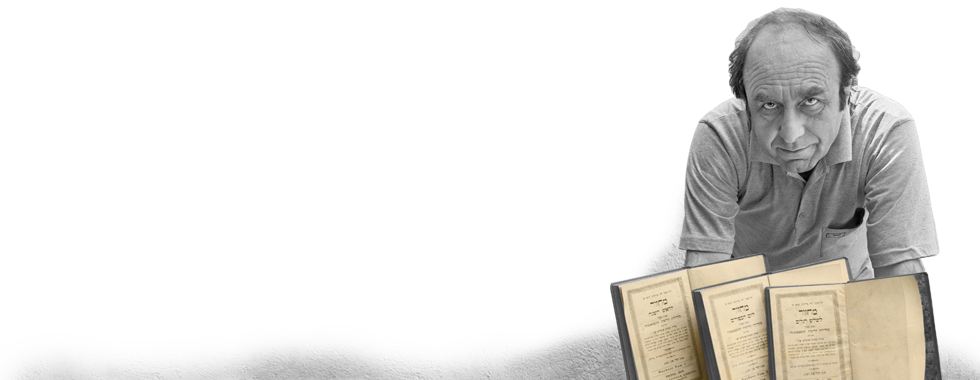

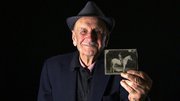

Norman H. Gershman

Norman Gershman has been a photographer for over 30 years. In 2002, Norman was doing research for a photo essay on righteous gentiles - non-Jews who rescued Jews during the Holocaust. He heard about the unique story of Albanian bravery during WWII: that the entire country, including the government, refused to collaborate with the Nazis, even while under a brutal occupation.

When he learned that Albania was 70% Muslim, Norman knew he had his next project. “French saved Jews, Poles saved Jews, Ukrainians saved Jews, many people saved Jews,” he said. “Muslims? What, are you crazy? That’s the story.”

It was a story that few knew, because Albania was sealed off from the outside world for almost 50 years by the xenophobic dictatorship that followed the end of World War II. Norman became determined to rescue and record this untold story of bravery and compassion. “These people are good people. They’re true heroes.”

His tireless efforts to identify and document the stories of the many Muslim Albanians who sheltered Jews during the war became the basis of our film, Besa: The Promise. Indeed, without Norman’s years of research, investigation, and old-fashioned detective work, the film would never have been made at all.

Beginning in 2007, the Besa: The Promise film crew made two trips to Albania with Norman, and also a trip to Israel where his portraits were exhibited at Yad Vashem. Since then, Norman’s photographs - together with short excerpts from the documentary - have been at the United Nations’ Headquarters in New York, and at the European Union Headquarters in Strasbourg, France. In 2008, Syracuse University Press published a book of Norman H. Gershman’s portraits, Besa: Muslims Who Saved Jews in WWII. Uniformly praised in numerous reviews, it has also been featured by CBS News, NPR, Voice of America and Al-Jazeera. Over a dozen exhibits of Norman’s work will open in the US, the UK, Israel, Italy and Albania.

Norman founded the Eye Contact Foundation, a 501 (c) (3) nonprofit corporation promoting peace and unity, serving as its Executive Director.

Rexhep Hoxha

Rexhep Hoxha lives in Albania’s capital city of Tiranë with his wife Bardha, son Ermal and daughter Romira. He owns a small toy store, which is adjacent to the family home where his parents and grandparents also lived.

Rexhep was a teenager when his father told him about rescuing a Jewish family during WWII. His father, Rifat, was a humble man, and didn’t go into much detail. It was something that many Albanian families did, it was their Besa, their duty to protect others in need.

After the war, Albania was ruled by a xenophobic communist dictator named Enver Hoxha - no relation. Hoxha is a common Albanian name. It means imam, a Muslim cleric. In fact, Rexhep’s grandfather had been an imam. But under the communist regime, religion was outlawed, and Rexhep grew up watching his father practice his Muslim faith in secret, carefully bringing the family Qur’an out from its hiding place.

Along with the Qur’an, Rexhep’s father kept another secret: three Hebrew books left behind by the Jewish family he had protected for six months during the war. When the family fled Albania, they asked Rifat to keep the books. To carry them was dangerous and would give them away as Jews. They hoped to return for them one day.

But the Jewish family never came back. Rexhep promised his father he would find the family and return the books. It remained a dream for decades, stifled by the communist government which didn’t allow any communication with the West and would have burned the books had they been discovered. Rexhep worried that he would have to pass his promise to his late father - his Besa - to his own son Ermal.

Then Rexhep met Norman Gershman and told him his father’s story. He showed him the Hebrew books and asked, “Can you help me find the Jewish family?”

Thus begins a journey across cultural and religious divides. Through Rexhep’s quest to fulfill his besa, Besa: The Promise brings a contemporary twist to the telling of Albania’s remarkable history in rescuing Jews in WWII. It is a story of courage, perseverance, love, and honor. It is a story of exploration and discovery; a story of fathers and sons, Muslims and Jews.

Orhan Frasheri

Orhan Frasheri had just completed high school and was working as an accountant when the Italians occupied Albania in 1939. Orhan’s father, Halil, opened their large home in Berat to partisans resisting the occupation.

The director of the company where Orhan worked called him in. “He asked me to fill out a form of fascist party membership, which I refused. I was then fired. Seven members of my family and I joined the partisan’s liberation movement.”

Orhan’s family were Bektashi. “My father was very religious. He followed all the rituals. My uncles were also religious.”

One day, a friend told Orhan’s father about three Jewish families fleeing the Nazis. “Father took them in, and accommodated them on the second floor, giving them beds, mattresses, blankets, dishes, everything. They offered to pay for them, but my father did not accept that. They also had some jewelry, and since father did not accept money, they tried to convince him to take that. But he told them we would take care of everything.”

Some of Orhan’s neighbors were surprised that a pious Muslim like his father would take in the Jews. “But father said, because he was a religious man, because he was Bektashi, we will open the doors for them. Religion was not an obstacle in the house. The real obstacle was that having them in our house was like having a time bomb. They were followed at every step. Yet we accepted them regardless the consequences that we would suffer if the Gestapo found them.”

Orhan also attributes his father’s willingness to shelter the Jewish families to the Albanian code of honor, Besa. “The Besa of an Albanian is more valuable than a golden bar. Albanians have pledged their Besa, their word, before gold. There’s a saying that an Albanian would rather sacrifice his son, than break his Besa.”

Orhan was photographed by Norman H. Gershman for his book Besa: Muslims Who Saved Jews in WWII.

Myzafer & Luleta Kazazi

Myzafer and Luleta Kazazi are from an Albanian family of seven sisters and three brothers. Luleta was the youngest, born in Tiranë during the war. “I was two when the Jewish immigrants came. According to my mother, they named me Luleta.”

The Jewish immigrants were the Amarilio family - David, Fatima, their daughter Matilda and their son, Solomoni - who fled from Yugoslavia to Albania when the Nazis advanced on the Balkans. Myzafer explains how they gave the Jewish family Muslim names to protect them. “David was Daut; Fatima, Fatma; Matilda was Hatixhe, and Solomoni was Muharrem or Memo. These were nicknames so that they won’t attract any attention as Jewish.” Incredibly, all of the Kazazi’s neighbors knew about the Jewish refugees, sometimes assisting in hiding them from house to house as the Nazis made random sweeps through the neighborhood. Myazafer recalls with pride how the whole country helped Jewish refugees. “During the war the Jewish refugees were protected by Albanians, who through a nationwide system of care and information worked secretly to protect them and helped them to move from one place to another and avoid any possible contact with the Nazis.”

The Kazazi’s household was a crowded, but happy. “My father, says Myzafer, “was the kind of person who could handle any kind of difficulty with courage. And he was the only one working and had to feed ten children – understand? That’s why as soon as Albania was occupied by Italy, he immediately turned half of the house into a bakery, so that he could provide enough food. And because of the bakery, we never suffered for food and he was able to support the Jewish family also. That was the humanity that characterized my father.”

The differences between the religions of the two families were never an issue, and they joined in each other’s holidays. “The Marvelous Allah wants people to love each other,” Myazafer says.

After the war, the Kazazis were unable to communicate with the Amarilio family because of the era of communism. “I know Solomoni is in Israel and is a violinist,” Myazafer says. The Amarilio family remain in the hearts of the Kazazis. Luleta recalls, “They fed me, they put me to sleep, washed me up. And I loved them.”

The Kazazis were photographed by Norman H. Gershman for his book Besa: Muslims Who Saved Jews in WWII.

Jasa Altarac

In April of 1941, seven year-old Jasa Altarac was visiting his grandmother in Sarajevo. The entire family had come together for Passover. Suddenly, the sound of Luftwaffe bombers filled the air and the family rushed into the basement. The house took a direct hit. “I remember flying in the air for some three floors or something like that and falling down. My little sister, Lela, was found together with my grandmother. Dead.”

After the funeral, Jasa and his parents returned to Belgrade. “The Germans were already there, of course. And it was posted throughout the city that whoever helps Jews will be shot dead. All the Jews had to report to the police commander. So my father went to report himself and was sent to forced labor.”

The family decided to leave for Albania, because it was under Italian jurisdiction, “and the Italians did not persecute Jews.”

The Altarac family ended up in Kavaje, Albania. Every day, the head of each Jewish family had to report in to the Italian commander, but then they were free to go. The children, like Jasa, went to an improvised school, with an Italian soldier as their teacher.

As a city boy, Jasa had to adjust to the rural life in Albania. “I remember the fields, they were growing wheat there. I was fascinated with the ears of wheat, they were so plump and so … big. And I took one and examined it. And the farmer came, an old man and he said that, ‘Yes, we have a good year. Allah knoweth that we have the Hebrews and we need food. So we have a good year.’ So, this was in fact very typical of Albanians - to show a good attitude – a good sense of hospitality to everyone.”

In September of 1943, the Italians capitulated to the Allies. Soon Albania would be occupied by the Nazis. “The Italian commander assembled the heads of the Jewish families and told them, ‘We are leaving town. You should know that we have destroyed all documents that show that you were here.’ At he same meeting, the mayor of Kavaje gave to every head of the family documents which said that they are citizens of Kavaje and are Muslim.”

The Altarac family decided they would be safer in the bigger city of Tiranë once the Nazi occupation force arrived. They were sheltered by the Atif & Ganimet Toptani family. The Altarac family celebrated Passover with other Jewish families, including the Mandils who were protected by the Veselis, and the Gershons who were protected by the Frasheris.

There were many dangerous times during which the Nazis would search for Jews. But the Jewish families were protected by their rescuers and neighbors. Everyone knew and no one told. “People would knock on the door in the middle of the night. They would give them shelter. They would give them food. They would calm them down. ‘Be calm. Nothing will happen to you. We will guard you. They will kill us before they kill you.’”

After the war, the Altaracs returned to Belgrade, then moved to Israel in 1948. By then, Albania was under the dictatorship of Enver Hoxha and all contact with the West was prohibited. “We could not contact the Toptani family. We understood very well what was going on in the Communist regime. We didn’t dare ask about them, so lest it be taken against them.”

In 1992, Jasa Altarac petitioned Yad Vashem to have the Toptani family listed as Righteous Among the Nations. In 2000, he also petitioned on behalf of the Gershons to have the Frasheri family declared Righteous as well. “There is a sense of gratitude that I owe to these people. The Albanians are good people.”

Mehmet Frasheri

In May of 1943, Mehmet Frasheri was a young man of 18 years. His life was far from that of a carefree teenager - his country, Albania, was occupied by the Nazis. And yet, he didn’t hesitate to take charge of the Jewish family a villager pointed out to him. Mr. Gershon, his wife and two daughters escaped from Macedonia and were seeking shelter. Mehmet brought them to his family’s farm outside of Tiranë.

“Our religion is Muslim. We took them under our protection because of our family’s moral that we should save these souls who were suffering and being killed for no reason, because they were good people, innocent people.”

Not long after the Gershon family arrived, there was a knock at the door. “The person told my father he was a Jew and didn’t know where to hide. ‘Come in,’ my father said.” This was Mr. Gertwill.

“There were two extra rooms that my father made for the workers. In one of these rooms, we put Gertwill. Each morning, I used to take a package of tobacco and give it to him because he used to smoke a pipe. He greeted me with ‘Danke! Danke!’ Eheee… They were good people.”

The Frasheri’s farm became somewhat of a gathering place for Jewish refugees who would come to see Mr. Gershon, who acted as their spiritual leader. “My father always said the religion of the Jews and Muslims is very similar,” Mehmet recalls, “such as fasting on Friday. Mr. Gershon would have me go to the market on the Sabbath to get the lemons he needed for rituals.” The Jewish refugees stayed with the Frasheris for over a year, until the end of WWII. “When it came time to leave, they cried, we cried. We were like a family.”

As the communists came to power after the war, communication with the West was restricted. “There was no more contact with the rest of the world, especially with places like Israel, ohuuu! It was hard - very hard.”

More than 50 years later, Mehmet Frasheri and his parents Hysref and Ermine, were honored on the Wall of the Righteous Among the Nations at Yad Vashem.

Mehmet was photographed by Norman H. Gershmanfor his book Besa: Muslims Who Saved Jews in WWII, and interviewed for Besa: The Promise. Since the interview, Mehmet passed away. Witnesses to this forgotten history are all elderly and gathering these stories before they pass was a great motivation to Norman. “It’s a race against time,” he says, “A race with history.”

Rina Mandil Nahum

In April 1941, two-year old Rina Mandil was walking home with her brother and mother after shopping in Belgrade. Suddenly, her father, Moshe, appeared before them. “Turn around and walk the other way,” he said, “the Gestapo are at our apartment searching for us.”

The family never returned to their home, instead staying with friends until they ended up in Pristina. They were put into an Italian-run prison with 120 other Jewish families. Rina recalls, “The conditions were very tough. We had lice, they shaved our heads. It was cold, very crowded and there was no toilet, only a pit.”

After about a year, some Nazi officials arrived. “They came one day to the prison and said, ‘You’re crowded? We’ll help you by making it less crowded.’ Fifty names were selected off a list. As a young girl I watched. It was something terrible, breaking up families, and there was a lot of crying and screaming. And we knew they weren’t coming back.”

Rina doesn’t recall exactly how her family left the prison. By 1942, the Nazis were pressuring the Italians to send them all the Jews. The Italian commander of the prison instead deported the remaining families to Albania.

“We arrived in Tiranë. There was a photo studio there, and the name was very familiar to my parents. It turned out that it was owned by one of my grandfather’s employees who learned the profession from him. And they went in. The meeting was very emotional, hugs and kisses, and, of course, they know how to receive guests. Extraordinary. It’s one of their ten commandments, how they must behave to strangers and guests. He welcomed us and said there was nothing to discuss. He would hide us in his home.”

Because Rina’s family had run a photography studio in Belgrade, Moshe was hired as a photographer. A teenage Muslim boy, Refik Veseli, also worked at the studio. Moshe taught Refik how to refine his techniques, and Refik covered for Moshe when the Nazi occupiers came into the studio to have their portraits taken. “There was a black cloth that the cameras used to have in those days. You cover yourself and take the picture. And none of the Nazis who came to have their picture taken knew that under the black cloth was a Jew.”

The situation in Tiranë became even more dangerous. Refik contacted his parents who lived in Kruja, a small mountain village. They agreed to hide the family. “They took such a big risk to hide us. And with no hesitation, even if it cost them their lives. They simply extended their hearts.”

After the war, the Mandil family returned to Yugoslavia and took Refik with them. “He was like family. My father taught Refik a profession for life.” But as Eastern Europe fell under communism, the Mandil family decided to emigrate to Palestine. They asked Refik to come with them. “But at the last minute he was afraid the communists would take revenge on his family in Albania. They knew that he came with Jews. So he stayed. We corresponded for a short period, but then it was prohibited. Albania was the last country to open up. They didn’t allow anyone in, and no one was allowed out.”

Finally, in 1987, Rina and her brother arranged for Refik to come to Israel, where he was honored at Yad Vashem as the first Albanian to become Righteous Among the Nations for rescuing the Mandil family. Refik’s parents and brothers, Hamid & Xhemal, were honored later. “Albanians gave their souls for us. The Veseli family…ah…there was a great love. My father loved Refik like a son.”

Hamid & Xhemal Veseli

Hamid, Xhemal and their older brother Refik share the distinction of having their names inscribed on the wall of Righteous Among the Nations at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem for their roles in rescuing Jews during WWII.

Xhemal was the youngest of the brothers, only about thirteen during the war. Two Jewish families, the Mondils and the ben Josifs, survived the Holocaust because of the bravery of the Veseli family protecting them.

Many Albanians took in Jewish refugees and although their neighbors knew, no one betrayed their guests. Xhemal and Hamid quote an Albanian proverb, “Our home is our guest’s house, then our house, but above all, it is Besa: The Promise.”

During the very dangerous occupation of Albania, the Nazis would stage sweeps through Tiranë looking for Jews. Refik, Hamid and Xhemal would lead their guests out of Tiranë to mountain villages like Kruja. Xhemal explains, “The peasants came to sell their products in the market twice a week. And I said we must find some village costumes. We dressed up like peasants and walked behind the animals amongst the villagers.” But even so, crossing the Nazi checkpoint was risky. Xhemal recalls, “I don’t know how to explain the fear that we felt, because if we had been discovered by the Nazis, they would have executed us all – the villagers along with us.”

The checkpoint blocked the road with a wooden beam. “To tell the truth, our knees were shaking from fear. It was a decisive moment – of life or death.”

To Xhemal’s great relief, the guards lifted the beam and waved them through. “Once we crossed the checkpoint, we started crying from the joy.”

Hamid remembers that the family wanted to pay for the expenses, “But of course, as Albanians we never accept any money from the guest because it is not normal that guests pay.”

Xhemal says the decision to help the Jewish families came from their Muslim faith. “The Qur’an says that we should always help people that are in difficulty regardless of religion or race.”

The Veseli brothers were photographed by Norman H. Gershman for his book Besa: Muslims Who Saved Jews in WWII. Since the interview, Hamid Veseli passed away. Gathering these stories while the witnesses are still alive is a great motivation to Norman. “It’s a race against time,” he says, “A race with history.”

Hajji Reshat Bardhi Dedebaba

Hajji Reshat Bardhi Dedebaba is the leader of the charismatic Muslim sect known as Bektashi. “We are the most liberal of Muslims. Bektashi see God everywhere, in everyone. God is in every pore and every cell, therefore all are God’s children. There cannot be infidels. There cannot be discrimination. If one sees a good face one is seeing the face of God.”

The role of Albanian Muslims in saving Jews in WWII was exemplified by the government leaders at that time, the Baba explains. “The Prime Minister of Albania was a Bektashi. When Jews were refugees, he asked Albanians to take their children in, to let their children sleep together. To share their food with them.”

The Baba emphasizes that, “The Jews were protected not only by Bektashi, but by all Albanians – without distinction of religion and race.”

After WWII, Albania came under the communist dictatorship of Enver Hoxha, who banned religion. Many religious leaders who refused to bend to the communists’ mandates were executed or sent to hard labor camps. Between 1958-1968, the Baba was incarcerated in a communist “re-education” camp. His only crime: being a Bektashi baba, a member of the higher clergy, and one of directors of a Bektashi organization. After 1967, he was bound to a compulsory labor camp for the next twenty-three years.

Since 1991 and the rescinding of the order abolishing religion, the Baba has helped restore the Community of Bektashi, the reconstruction of religious objects damaged during the communist regime and the restitution of faith all over Albania and beyond. “May God bless peace and unity for all the entire world, be that in the East or in the West! Amen!”

The Baba was photographed by Norman H. Gershman for his book Besa: Muslims Who Saved Jews in WWII. Hajji Reshat Bardhi Dedebaba passed away in April 2011.

Leka I Zogu

On April 5th, 1939 the cannon sounded in Tiranë announcing the birth of the son of King Zog and Queen Geraldine, Leka I Zogu. Two days later, his parents had to flee Albania when it was invaded by the Italians, then allies of the Nazis. The infant Crown Prince began life in exile, unable to go back after WWII because of the communist takeover. In 2002, Leka I Zogu finally returned to Albania.

The crew of Besa: The Promise was on location when Leka I Zogu was photographed by Norman H. Gershman for his book Besa: Muslims Who Saved Jews in WWII. A portion of the filmed interview is included in the documentary.

Norman asked Leka I Zogu what prompted King Zog - Europe’s only Muslim monarch - to open Albania’s borders to Jews in 1938, knowing that he could have had the full wrath of the Nazis turned on his country.

“Why did he allow the Jews to come? Because he felt it was not a human act that the Germans would carry out. He felt, give the Jews a break, give them a way out.”

Did Leka I Zogu know how many Jews King Zog personally saved? “He didn’t really talk about it. I once heard that 400 passports were handed out. How many more visas, I don’t know.”

It has been estimated that nearly 2,000 Jewish refugees were saved in Albania, its citizens following their tradition of Besa and the lead of King Zog in taking a stand against the Nazis.

Leka I Zogu passed away in November 2011.

Edip Pilku

Edip Pilku was 12 when the Jewish family came to stay in his home. He was the son of an Albanian engineer and a German mother. “My mother was Protestant, whereas my father was Muslim. My mother practiced all the rituals of Islam. She would go to the mosque and cover her head. She fasted during the Holy Month of Ramadan and celebrated Bajram. Because she loved my father so much she learned all the Albanian traditions. My father was an intellectual. He knew five languages and was very much in love with my mother. They had a good relationship. “

Edip’s father designed the beautiful mosque in Durres, the seaside town where they lived. One day his father noticed a man painting a picture of the mosque and struck up a conversation with him. Learning the man was German, Mr. Pilku invited him to bring his family to visit.

The Gerechter family arrived in Albania in 1939, after King Zog opened the borders to any Jews that wanted to come. The Pilkus decided to shelter the Gerechter family. Their daughter, Johanna, was about Edip’s age, and they became as close as brother and sister. To avoid suspicion, they called her by the Albanian name Juta. “My mother spread the word that they were her relatives from Germany.”

But in 1943, the Nazis occupied Albania. “I remember hearing my father saying to my mother that the Nazis were coming to search because they have learned of the presence of Jews. I could understand they were in great danger.” Edip’s father took Mr. Gerechter to a small village in the mountains for safety. The Nazis came to search the Pilku home - twice, and Edip’s mother stared them down. “My mother said, ‘Are you that suspicious to not believe a German woman? I don’t know any Jews, so you are wasting your time here and if you come here again I’ll complain.’ They saluted her and left.” The Gerechter family stayed with the Pilkus until the Allied invasion pushed the Nazis out in November 1944. The Communists took over Albania, and for nearly fifty years Albanians were not allowed to communicate with the West.

Little Juta never forgot the bravery of the Pilkus, and in 1997 petitioned to have them declared Righteous Among the Nations. Today, the names of Edip’s parents, Njazi and Liza Pilku, are etched on the wall in the Garden of Remembrance at Yad Vashem in Israel. Photographer Norman Gershman met and interviewed Edip for his book Besa: Muslims Who Saved Jews in WWII.

Johanna Neumann

Johanna Gerechter Neumann was born into a family of merchants in Hamburg, Germany. She vividly remembers walking to school in November 1938 and seeing crowds of people throwing stones into the synagogue window, the Torah scrolls and Judaica scattered in the street. It was the continuation of Kristallnacht, the night of the pogroms.

“Somehow my mother had found out that the king of Albania, King Zog, told his border police that if Jews came and wanted to enter the land, not to ask questions but to let them come in.” In 1939, they arrived Albania. “The culture shock was tremendous, to put it mildy…”

For an observant Jewish family, life in Albania - a predominantly Muslim country - was a revelation. “We heard the muezzin call the faithful to prayer, five times a day, and that sound is so familiar to me that when in this day and age I hear the same it’s very heartening to hear it again. When we went to the mosque, it was interesting how they do things similar to the way Jews do it in Islam.”

The Gerechters remained in Albania, fleeing from one town to another, staying one step ahead of the Nazis, who occupied Albania in the summer of 1943. The last family that sheltered them, the Pilkus, are remembered with great fondness. They had a son, Edip, who was about Johanna’s age and they became like brother and sister.

Because Mrs. Pilku was from Germany, their home would often get visits from the occupying forces. During these dangerous times, even the children knew they had to protect their Jewish guests. “Whenever anybody asked the family, ’Who are the people that are living with you?’, they would say, ‘These are my mother’s cousins from Germany and they are visiting with us.’”

The Gerechters sheltered with the Pilkus until the Allies arrived in 1944. Today, Johanna lives in a suburb of Washington, DC, where she volunteers at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum and has written a memoir, Via Albania. “Albania and Denmark are the only two countries where the government actively helped the individuals to save Jews. The government did not collaborate with the Germans.”

In 1997, Johanna petitioned Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Memorial in Jerusalem, to include the names of Edip’s parents, Njazi and Liza Pilku, on the wall in the Garden of the Righteous. “It took two or three years to put all the documentation and everything together to have the Pilkus honored as Righteous Among the Nations. Because I really wanted the family to know that their grandparents and parents were wonderful people who self-sacrificed themselves for Jews.”

Rashela Lazar

It was Ramadan, 1943. Rashela Lazar, a Jewish Yugoslavian girl of 16, was being sheltered by the Hoti family during the Nazi occupation of Albania. Rashela was determined to fit in and tried to follow the required fasting of this important Muslim holiday. But her generous Albanian hosts had other ideas. “There was the son who lived in the courtyard, who would bring me food during the day. No one knew about it, not even the grandmother. So, in the morning and at night I wouldn’t get up to eat. The old woman would come and say, ‘Poor thing, isn’t coming to eat. She’s fasting.’”

The Hotis took an extraordinary risk in sheltering Rashela. During the occupation of Albania, the Nazis stationed a garrison at the Hoti family compound in Shkodra. Their courtyard was filled with military vehicles. Their barn was filled with Italian prisoners of war. The first floor of their house was where the Nazi soldiers lived. The Hotis moved upstairs with Rashela. “The floor was wooden planks. And there was a crack between the planks. And I saw from upstairs that there were Germans downstairs. I would watch them. And I was scared to death.”

Rashela’s family was in hiding elsewhere in Albania. She missed them terribly, and worried for their safety. “I was afraid of the Germans. You don’t know that kind of fear. I always thought the word ‘Jew’ was written on my forehead. If they caught me, they would catch my father, my mother, my sisters, everyone. If they had found me, the Hoti’s whole courtyard would have gone to hell. The Nazis would kill them with pleasure. To kill a Jew - even more of a pleasure.”

When Rashela had to go outside, she borrowed the traditional veil and clothing from one of the Hoti’s daughters. “I dressed like a Muslim, I did what Muslims do. I ate meat with cheese. I didn’t practice the Jewish faith, I observed the Muslim faith. That’s a point I’d like to make, actually, because the Muslim Qur’an doesn’t say to kill Jews.”

During the year that Rashela was sheltered by the Hotis, she grew very close to the family. “One of the sons was very good-looking. A handsome guy, tall. So, I was young, and there was a war. I fell in love with him. And he fell in love with me, but I was afraid to start anything with him. I said, God forbid I should get pregnant! Oh & what a tragedy that would be. But I told him I loved him. When the war ended, they wanted me to marry him, but I didn’t want to stay there any longer.”

When it was time to leave, the parting was through tears. “It was leaving people who love you, for life. Sure, I cried. And they cried, too.”

Rashela reunited with her parents and sisters and eventually moved to Israel. She learned that her grandparents, uncles, many extended family members and friends had died at the Bergen Belsen concentration camp. In 1994, she petitioned Yad Vashem to have the Hoti family declared Righteous Among the Nations for having protected her. “It was no small thing that they did. It was great bravery.”

Vehbi Hoti

Vehbi Hoti was six years old when the Nazi trucks rolled into his family’s courtyard in Shkodra, Albania. It was September, 1943. Italy had capitulated to the Allies and the Nazis pushed in to Albania. The Hoti’s large compound, where his extended family including aunts, uncles, cousins and grandparents lived for more than three hundred years, attracted the attention of the occupiers. They needed to situate their garrison and they asked if they could use our property. My father and my uncle said yes, with no questions asked. We all knew about the cruelty of the Germans.

The courtyard where Vebhi and his brothers played ball soon filled with German soldiers, vehicles and munitions. Seven Italian prisoners of war were kept in the chicken coop. The Nazi soldiers took over the ground floor of the family’s house. The Hotis all moved upstairs.

Shortly after, one of the cousins came to VehbI’s father with a request: A Jewish family from Pristina with four daughters was in need of shelter. Could they take in one of the girls? My father reflected this way: We cannot say no to someone in trouble. We cannot close the door on her, but will take her in.

Vehbi recalls that while his father, Hasan, had little formal education, he was quite a formidable man. He had intuition, intellect and was religious. We still quote his sayings. Hasan Hoti was following the Albanian tradition of besa. “There is an expression: Ne bese tane - under your given promise. My life is in your hands. Albania - apologies for any lack of modesty here - is known for this.”

Rashela Lazar came to stay with the Hotis. She was sixteen, the same age as Vehbi’s sister. “We didn’t want the sound of her name to attract the attention of the Germans, because they would realize that it was a Jewish name. Since we were Muslim, we wanted them to think that there were only Muslims in the house. To hide her identity, we gave her the name Shpresa, to give them the impression that she is a member of our family. If she kept her real name, it would be like suicide. ”

Whenever Rashela ventured out of the house into the courtyard, she wore the clothes of Vehbi’s sister, including the traditional veil. In the face of certain death should Rashela be discovered, the courage of the Hoti family never faltered. The Koran says that no one should break the besa, even if you have to give your own life. And my father and uncle were convinced that the Germans would search everywhere for their prey except in the den in which they lived. This assured them, and they turned out not to be wrong.

The Hotis protected Rashela until the end of the German occupation in November 1944. “I remember the moment when she left our house. She was crying and we were crying because we were close. She became like a sister. ”

After the war, Rashela reunited with her family and moved to Israel. “We received two letters. Our father said my brothers, ‘Look - we did what we had to do, that is, we took her in. But don’t respond. The time will come and we will be questioned about our relation with them.’ He was talking about the new communist system that had just been established. And we didn’t reply.”

But the Hotis never forgot Rashela during the next half century. Finally, in 1990, after the communist regime ended, Vebhi saw a newspaper article and heard on radio about a Jewish lady looking for the Hoti family. They reestablished contact through the Albania-Israel Friendship Society. I finally went to Israel in 1998, on the 50th anniversary of the creation of the state of Israel. When we first saw each other, we both cried. It was impossible for me to avoid the tears, as it was for her as well. Thanks to Rashela our names are on the wall at Yad Vashem museum.

Rashela offered gifts and money in gratitude for the Hotis having helped her family. But as Vebhi explains, Although Albania is a poor country, the greatest need is not a material need. A moral need brought us here. The need to see each other’s eyes.

Vebhi is understandably proud of the role of his family and country in rescuing nearly two thousand Jews during the Holocaust. “I stress this one more time: it was not a tradition just of my father and the uncle, it was all Albanians. To us doesn’t matter whether one is Catholic or Jewish or Muslim, a knock on our door is enough. We say, ‘Come in!’ There is no religion that cultivates hate, killing, pillaging and plundering. Mosque is good. Church is good. Synagogue is good. God says help each other.”

Vehbi was photographed by Norman H. Gershman for his book Besa: Muslims Who Saved Jews in WWII.

Verushe Babani

Verushe Babani was 16 years old when her father sheltered Nisim Behar and his wife. While she doesn’t remember many details of the sheltering, she recalls her mother one day asking her father where his new winter coat was. “He had given it to the Jewish man,” Verushe told Norman Gershman, who interviewed her for his book, Besa: Muslims Who Saved Jews in WWII.

Her father not only gave the Jewish refugee his new coat, but gave him a job managing his clothing store. Such generosity was typical of her Muslim family. “That’s how they were,” she told Norman, smiling radiantly. “Everybody did it.”

Shortly after Norman interviewed Verushe in 2007, she passed away.

Yeoshua Baruchowic

Yeoshua Baruchowic stood watching the Nazis trucks roll into Pristina and trembled with fear. He had already been assigned to forced labor and made to wear a Star of David on his shirt. “No, no, no,” he said, “I don’t want to die. I will leave this place.” The year was 1941. He fled, thinking he would fare better in Italian-occupied Albania. To his surprise, the Albanian people embraced and protected the Jewish refugees.

Even though it was illegal for him to work under the facist regime, Yeoshua found a job as an assistant to an Albanian dentist, Dr. Jidar, who took him in. One day, one of the other assistants came to Yeoshua and asked him to carry a secret letter to a someone in Shkodra. Upon arriving at the destination, Yeoshua was surprised to see the recipient of the letter was his own brother, who had joined the Albanian Resistance. Yeoshua joined as a partisan. Both he and his brother fought for Albania’s freedom, suffering wounds in battle.

The Italians capitulated to the Allies in September 1943, and immediately the Nazis stormed in to Albania. Yeoshua and some of his fellow partisans were questioned by Nazi troops and told their papers were not in order. Taking them to a police station, Yeoshua slipped some money to a guard, pleading to go to the toilet. Once out of sight, he took off running.

He made his way to a tavern owned by Ali Sheqer Pashkaj. Yeoshua told Ali he was running from the Nazis and that he needed help. Ali instructed him to hide in a certain place up in the mountains, and that he would come for him later.

Yeoshua ran through the woods and found the spot, laid down and covered himself with branches. Throughout the night, he was sure he would be found. Meanwhile, Ali invited in the Nazis looking for Yeoshua and got them drunk. The next morning, they returned, furious that the Jew had gotten away. They took Ali out to the square and put a gun to his head., threatening to kill him and burn down the village if Ali didn’t tell them where the Jew was. Finally, learning nothing from Ali, they left.

Ali immediately went to where Yeoshua was hiding. “I didn’t think he would return, but he said, ‘besa, besa’which means a promise.”

Yeoshua lived with Ali’s family for the next two months. He observed the Muslim family in prayer five times a day. “They said, ‘Allah, Allah’ but I knew they were praying to God.” And he was grateful for their protection. “If the Nazis found a Jew with a family, they would take grave reprisals. Burn the house. Kill the owner.”

After the war ended, Yeoshua moved to Mexico and became a dentist. He was the only one of his family of thirteen to survive the war. “Mother, father, sisters, brothers… I weep not only for myself, not only for my family, but for all six million people. One million three hundred thousand were children. They all went up in ashes.”

Because of the decades of communism that followed WWII in Albania, Yeoshua was never able to reconnect with Ali. But in 2007, he traveled to Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, Israel, to meet Ali’s son Enver at an exhibit of Norman H. Gershman’s portraits of Righteous Muslims.

JWM Productions, LLC

JWM Productions specializes in innovative, immersive and character-driven films and storytelling. Started in 1996 by two multiple Emmy Award-winning filmmakers, Jason Williams and Bill Morgan, JWM Productions has made over 300 hours of thought-provoking and engaging television series, docu-soaps, specials, shorts, ob-docs, commercials and documentary films.

Today, JWM ranks among the world’s leading independent producers of factual entertainment.

Jason Williams – Producer

Jason Williams is the multiple Emmy Award-winning President and co-founder of JWM Productions, LLC. His films have engaged such diverse subjects as marine technology, ancient history, current affairs, natural history and anthropology. His productions have taken him to more than forty countries, six continents and several war zones.

He has been published on the OpEd page of the New York Times, profiled in the journal Current Anthropology, and featured – for his documentation of archaeological sites in post-invasion Iraq – on the front page of the Wall Street Journal.

Bill Morgan – Producer

Bill Morgan is the Managing Director and co-founder of JWM Productions. In the last fourteen years, he has executive produced more than two hundred hours of documentary programming that, collectively, have aired on almost all major US and overseas cable and broadcast networks.

He first partnered with Jason Williams while making the landmark documentary series, Time Life’s Lost Civilizations, the sole winner of the 1996 Primetime Emmy Award for Factual Programming.

Bill Morgan’s prior work experience was gained in The National Geographic Society’s television division. While at National Geographic, he worked on over 100 segments for National Geographic Explorer and on National Geographic Specials for PBS and NBC.

Rachel Goslins – Director, Producer

Rachel Goslins’ most recent feature documentary, ‘Bama Girl, premiered at SXSW in 2008 and aired on IFC. Her first short film, Onderduiken, was about her family’s history in Holland hiding from the Nazis during WWII. She has made films for National Geographic, Discovery, PBS, A&E and History.

She was also the Director of the Independent Digital Distribution Lab, a joint PBS/ITVS project focused on distributing independent films online.

Rachel began working on BESA: The Promise in 2007 when the working title was God’s House. She spent two years tracking down Albanian and Jewish witnesses and filming them on three continents, as well many more weeks in the edit room reviewing dailies, supervising the editing of the first cuts, and working on the art direction and storytelling style for the animated sequences of the film.

Rachel is currently the Executive Director of the President’s Committee on Arts and Humanities.

Christine S. Romero – Editor, Producer

Christine S. Romero’s varied documentary film career includes multiple award-winning independent and broadcast documentaries for PBS, Discovery, National Geographic, History and NBC.

For more than 30 years, creativity flowed from Christine to enhance any project she produced or edited. She retired from film making in 2005, certifying at the Advanced Level as an Integral Yoga instructor. Sanskrit name: Brahmi – Goddess of Creative Energy.

Then she got the call to edit Besa: The Promise. Goodbye retirement, hello again long days. But this time, it’s dharma.

Neil Barrett – Director of Photography

Neil Barrett is a British cinematographer who has worked on over thirty broadcast documentary films for National Geographic, BBC, PBS, Discovery, History, NBC, ABC and CNN.

His work has won several awards, including a Columbia Dupont award for excellence in journalism and the Edward R. Murrow award for a documentary on the civil war in Liberia.

His films have been shown at the Sundance, Toronto, Fullframe, SilverDocs, Jackson Hole and Los Angeles Film Festivals. Two recent films were screened at the 2010 Tribeca Festival, on which one, The Woodmans, Rachel Goslins served as Creative Consultant.

Two of his feature documentaries – Kicking it (2008) and Everything’s Cool (2007) – have been released theatrically in the United States.

Philip Glass – Composer

Born in Baltimore, Maryland, Philip Glass is a graduate of the University of Chicago and the Juilliard School. In the early 1960s, Glass spent two years of intensive study in Paris with Nadia Boulanger and while there, earned money by transcribing Ravi Shankar’s Indian music into Western notation. By 1974, Glass had a number of innovative projects, creating a large collection of new music for The Philip Glass Ensemble, and for the Mabou Mines Theater Company. This period culminated in Music in Twelve Parts, and the landmark opera, Einstein on the Beach for which he collaborated with Robert Wilson. Since Einstein, Glass has expanded his repertoire to include music for opera, dance, theater, chamber ensemble, orchestra, and film. His scores have received Academy Award nominations (Kundun, The Hours, Notes on a Scandal) and a Golden Globe (The Truman Show). Symphony No. 7 and Symphony No. 8—Glass’ latest symphonies—along with Waiting for the Barbarians, an opera based on the book by J.M. Coetzee, premiered in 2005.

In the past few years several new works were unveiled, including Book of Longing (Luminato Festival) and an opera about the end of the Civil War entitled Appomattox (San Francisco Opera). The English National Opera, in conjunction with the Metropolitan Opera, performed Glass’ Satyagraha in London, April 2007, and the Metropolitan Opera presented the work in April 2008. Glass’ latest opera Kepler premiered with the Landestheater Linz, Austria in September 2009 and is currently working on an opera about Walt Disney that will premiere at the Teatro Real in Madrid in 2013.

His Symphony #9 was completed in 2011 and will be premiered in Linz, Austria in January 1, 2012 by the Bruckner Orchestra with a U.S. premiere in New York at Carnegie Hall on January 31, 2012 as part of the composer’s 75th birthday celebration. Symphony #10 has been completed this spring and will receive its European premiere in France in the summer of 2012.

Tom Schmidt – Art Director

Tom is Art and Animation Director for Percolate Digital. He and his wide and varied crew have created unique and memorable animation and VFX for everyone from Discovery Channel to ESPN to Imagine Entertainment.

Before that, Tom shepherded the world’s first digital delivery of news graphics for television stations around the world, as Graphics Director for Associated Press Television. He was won numerous awards.

Currently (and usually), he is somewhere in the hills, pedaling his bicycle.

Advisory Team

- Ambassador Akbar Ahmed, Chair of Islamic Studies, American University

- Dr. Janusz Bugajski, Director of the New European Democracies Project, CSIS

- Dr. John Esposito, Director of the Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding, Georgetown University

- Dr. Nancy Lutkehaus, Chair, Department of Anthropology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles

- Dr. Mordecai Paldiel, Former Director, Righteous Among the Nations Department, Yad Vashem

- Dr. Emad El-Din Shahin, Professor of Religion, Conflict and Peacebuilding, University of Notre Dame

- Dr. Graham Townsley, Managing Director, Shining Red Productions, PhD Social Anthropology

- Prof. Petrit Zorba, Chairman, Albania-Israel Friendship Society, Tirana, Albania